Eye For Film >> Movies >> Pink Belt (2024) Film Review

Pink Belt

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Every 30 minutes, we are told here, a woman is raped in India. Every day, six are gang raped. Then there are the acid attacks and the murders. Whilst misogyny is a problem around the world, it’s widely accepted – including by the country’s leading politicians – that it has a particular problem. It’s something that only really hit home for the young Aparna Rajawat when she cut her hair short and began passing as a boy so that she could train in martial arts. Suddenly she realised that it was possible to walk down the street without being stared at or targeted with degrading remarks. She could fly a kite or play marbles. She could go wherever she wanted. All these things she had been denied.

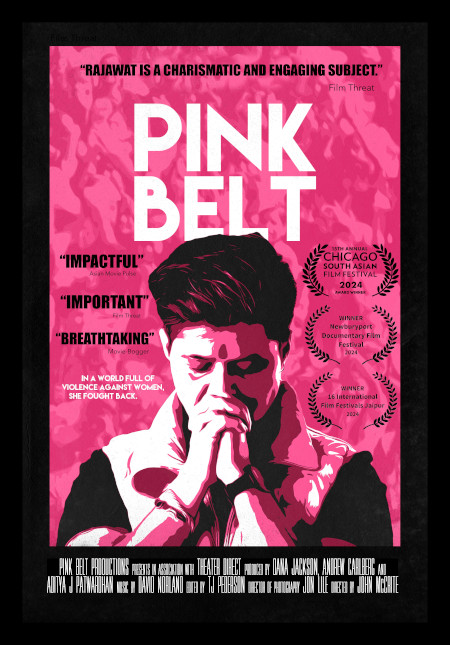

The 16 time martial arts national champion now runs Pink Belt, an organisation dedicated to teaching girls and women self defence, informing them of their legal rights, giving them access to education and empowering them in every aspect of life. We meet her here along with her patron, Mansi Chandra, who adds that “A woman is only strong if she’s financially empowered.” She owns a shoe factory which employs women, and we hear from one of her employees, previously trapped in an abusive marriage, who is now able to feed her children and pay their school fees.

Pink Belt is preparing for a Guinness World Record attempt, aiming to bring together the most women ever to learn martial arts moves at the same time, and the film charts its progress, building up to the big day, whilst expanding on its story. We visit the Rajawat family home and meet Aparna’s sisters. They may present themselves in a more traditional way, but they all have independent careers, something for which they credit their mother, who is sadly no longer around. We learn about the scheme whereby Aparna pretended to be attending drawing classes so she could get to training without incurring her father’s wrath, a ruse that failed when she won a competition and appeared in the news. She was an extraordinary talent, but her career ended when she was 17. In public she has always put this down to being hit by a truck, which is true, but not the whole of the story. Here she explains the rest, overcoming feelings of shame at her failure to assert herself more fiercely – but it’s hard to imagine many people doing so against such odds.

With more very personal revelations to come, the film demands a lot of her. Is it right that she should have to put herself through this? Yes, Mansi stresses, because part of what India’s women need to overcome is internalised shame, and she needs to be a role model for that. Furthermore, male power is rooted in the assumption that their word will always be taken over women’s. The more women who speak up, the harder that will be.

Amongst the women speaking here are acid attack survivors. One recalls being attacked at 14 after telling a suitor that she wasn’t ready to marry; another was attacked by her own father after reporting him for violence against her mother. They are badly, permanently scarred, but confidence and self care has made them beautiful. We see them laughing and smiling, and that matters, chipping away at the myth that such trauma inevitably ruins a life. It’s a powerful example for others who feel as if they have nothing left to live for.

Filmmaker John McCrite does a good job of pulling the different strands of the film together and giving it a sense of momentum. The women themselves always come across as shaping the narrative. Although it is vital to address suffering, the film does not linger on it. The past cannot be changed, and what matters is what happens now and in the future. What matters is all the other women and girls whose lives can be changed for the better. The focus is on practical solutions, which begin with awareness, and where that’s concerned, the documentary is part of the process.

Reviewed on: 14 Oct 2024